Increasingly, activists around the world are using digital tools to seek social change. In this online resource, activists and scholars document the use of digital tools for social change in different corners of the world. Beginning with a set of geographically diverse case studies, this site will grow to include essays on the changing nature of digital activism, examining ways these global case studies inform and challenge existing understandings of social change.

Read Global Dimensions of Digital Activism, and enjoy the introduction, below.

Introduction, by Ethan Zuckerman

Many articles and books have been written debating the validity of the “Facebook Revolution”. Those who see social media as a key factor in spreading the ideas of activism and protest cite Clay Shirky’s “Here Comes Everybody” and Howard Rheingold’s “Smart Mobs”, which document the ways in which peer to peer communications networks have mobilized large, adhoc groups. For example, international media coverage of the Arab Spring focused heavily on the role social media may have played in mobilizing participation in street protests. Reviewing a memoir by Egyptian activist Wael Ghonim, the New York Times titled an article, “How An Egyptian Revolution Began on Facebook”, tracing the Tahrir Square protests to the Facebook group Ghonim started to protest the brutal killing by police of Khaled Said.

Those who question the importance of digital communication tools in mobilization, however, cite Evgeny Morozov’s critique of online activism as “slacktivism” and Malcolm Gladwell’s argument that meaningful activism requires strong, offline ties to mobilize engagement. One way through this apparent conflict is to note that many of the people involved with organizing street protests see social media as a key tool; whether they are right or wrong about the potentials for digital media for social change, the perceived efficacy of these tools helps explain why so many people turn to them.

At the same time, the limits of digital media to transform governance are becoming apparent. Zeynep Tufekci’s work on the Gezi Park protests in Turkey suggest circumstances where social media drives thousands into the streets, but doesn’t meaningfully threaten people in power. Instead, she suggests that social media may make it easier to build large but fragile movements by making it easier to bring people into the streets, allowing organizers to forgo the hard work of compromise and coalition-building that used to be required to organize a large public protest. Opposition movements are highly visible and diverse, but lack the underlying structure they would need to threaten powerful institutions.

These lively and stimulating debates about the potentials and limits of online media for social change tend to overfocus on the relationship between social networks and street protests, the charismatic megafauna of activism. A broader view of the social media and social change ecosystem recognizes that there are paths towards change beyond mass mobilization designed to oust governments. Not every social problem is best solved by ousting those in power, and many valid theories of change focus on changing public opinion, influencing existing decisionmakers or other less abrupt paths towards change. To understand the possible significance of social media and social change, we need a broader understanding than we can get from considering the characteristics of protest in Tahrir and Taksim.

With this set of essays, we aim to broaden the understanding of the field of digital activism. Our project is inspired by digital activism researcher Mary Joyce’s ambitious attempt to build a database of cases of digital activism, the Digital Activism Research Project’s Global Digital Activism Data Set (GDADS). GDADS includes over 2000 instances of digital activism from 120 countries, sourced from news reports, specialist media like Global Voices, cases submitted to Joyce, as well as her own original research.

It can be challenging to study digital activism globally using quantitative methods, as it’s very difficult to know whether the database Mary has worked so hard to build is a representative sample of digital activism in the wild. (Jennifer Earl and Katarina Kimport’s important “Digitally Enabled Social Change” relied on data sets from e-petition and other activism websites, allowing the authors to construct representative samples from the data.) But the Global Digital Activism Data Set is an invaluable starting point for identifying case studies of digital activism. Working with Mary and other scholars and practitioners of digital activism, we set out to create an ever-expanding collection of case studies to broaden our understanding of activist strategies, tactics and results.

Rather than turning first to scholars of digital activism, we invited the activists themselves to reflect on their projects, their successes and failures and specifically, their theories of change. In dialogs with these activists and movement leaders, we’ve explored who activists thought they were likely to influence, whether their theories of change were successful and how those theories changed over the course of a campaign.

With support from the MacArthur Foundation’s Youth and Participatory Politics research program, we brought ten of these activists together in Istanbul, Turkey, along with students at Center for Civic Media and other activism scholars, including Mary Joyce and Phil Howard from University of Washington. Over the intervening year, we’ve worked with authors to develop and refine these case studies, and in July 2014, we are releasing the initial set of case studies to the web. This is the first round of a longer process; by releasing a set of cases, we hope to recruit other activists and scholars to the project, both to document additional cases of digital activism and to reflect on the cases showcased here, identifying larger themes and trends in the space.

Some of our first case studies show just how powerful these simple questions about intention and theory of change can be in understanding digital activism. Helena Puig Larrauri, who has worked closely with Sudanese pro-democracy activists, explores the ways that activists in an extremely dangerous political space have questioned risk/reward equations around visibility, first seeking to be visible to encourage protesters to come out in the streets, then realizing that building a sustainable opposition in Sudan will require the survival of the movements’ leaders. Sudan’s violent repression of protests has created a landscape significantly different than that of Tunisia or Tahrir Square and has led to digital activism strategies that seek change over the course of years and decades rather than days or weeks.

Gregory Asmolov’s history of Rynda.org examines how a volunteer response to an acute crisis in Russia turned into a sustainable model for mutual aid in Russia’s biggest cities. Activists found crisis response so rewarding that they continued their work even when Russia’s forest fires were extinguished. What Asmolov and colleagues have learned has implications for the disaster relief field as a whole and for organizers seeking to bridge online engagement and community participation.

Oleg Kozlovsky’s contribution also examines a Russian effort to use digital tools to build infrastructures that are absent or broken. His examination of an online election by the Opposition Coordinating Committee, the “non-systemic opposition” to Putin’s government, suggests that democratic activists can challenge an autocracy by running better and more transparent elections than the authorities in power. In the process, Kozlovsky and colleagues discovered just how challenging it is to run open elections, and provide a platform communities can use to carry out elections going forwards, even as such elections are disrupted by Putin’s allies.

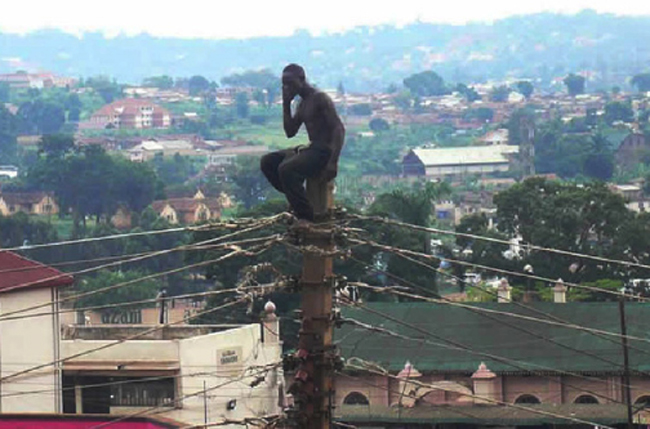

O’Seun Odewale’s examination of Light Up Nigeria also focuses on elections, in this case, on shaping the agenda of Nigeria’s 2011 general elections to include discussion of the massive nation’s strained and inadequate electrical grid. Odewale documents the transmedia activism used to build the Light Up Nigeria movement and shape political debate, but is unflinching in his recognition that the movement has not meaningfully changed Nigeria’s power problems and has lost momentum as a result. Successful mobilization and agenda setting are only one step in addressing a larger and more complex infrastructural problem.

What these four cases suggest is that our working method allows us to look at digital activism as strategies and tactics evolve over time. The shortcomings of most analyses of the Tahrir protests was an ahistoricity that saw the protests starting with Wael Ghonim, rather than 2008′s April Sixth youth movement or earlier labor organizing efforts. There is a tendency to focus analysis on success at the expense of failures, and to understand successful movement in terms of the strategy and tactics that led to a successful outcome. By asking participants and leaders of movements to trace the history of their involvement and the changing strategies, we see the ways in which digital activism fails, reconsiders and adapts. It is no accident that, in three of these four cases, the documented projects could be considered a failure. Most activist projects fail, and we often fail to capture, study and understand these failures as closely as we do with successes.

We are currently editing more case studies and hope to publish the next round in late summer of 2014, including an examination of womens’ rights movements in Pakistan, documentation of police abuse in Egypt and protests against poor electricity service in Nigeria. We are seeking more case studies as well, especially in countries and on topics we’ve not yet covered. If you are one of the leaders of a movement who’d like to work with scholars at Center for Civic Media to document and analyze your efforts, please get in touch with us.

As this project moves forward, we will be reaching out to scholars of digital activism to reflect on the case studies and help us identify broader trends in the space. Just in our discussions in Turkey, we identified some intriguing threads that ran through many of our first ten cases: an emphasis on satire and humor; a willingness to identify as “activist” but a refusal to accept the label of “political”; a trend towards building institutions that monitor state power or function outside state power. We welcome scholars in this space to follow the studies we post here and propose analyses for the second phase of this project.

We want to thank everyone who’s made this project possible: the MacArthur Foundation, students and staff at MIT’s Center for Civic Media and other academic institutions, and most importantly, the activists who’ve taken time to reflect, examine and share their experiences. We are grateful for what they do and for their fresh thinking about this important and expanding field.